bladder

bladder cancer

The urinary bladder is a hollow organ situated in the pelvic region that stores urine produced by the kidneys before its eventual expulsion from the body. Its elastic walls allow for expansion as urine accumulates, triggering the sensation of needing to urinate. The detrusor muscle, lining the bladder, contracts during voiding to expel urine through the urethra. Proper bladder function is crucial for maintaining urinary continence and overall renal health.

bladder cancer

Bladder cancer, constituting around 3% of Australian malignancies annually, primarily impacts individuals over 60, with a higher incidence in men than women. Smoking stands out as the predominant risk factor, significantly elevating the likelihood of developing bladder cancer. Additionally, exposure to certain occupational chemicals and chronic bladder inflammation may contribute to the increased risk in susceptible individuals. Regular screenings and lifestyle modifications are essential for those in high-risk groups.

Bladder cancer

The majority of bladder cancers at the time of diagnosis are low-grade and non-invasive.

the symptoms

Early-stage bladder cancer may not exhibit noticeable symptoms.

Common signs include painless haematuria (red or rusty urine), a burning sensation during urination, and occasional blood appearance over months.

Notable symptoms, when present, are related to tumour-induced irritation, manifesting as frequent, urgent, painful, or difficult urination.

If a tumour obstructs a ureter, patients may experience side pain between the ribs and the hip.

Tumour growth may constrict the urethra, slowing urine flow; bladder cancers can shed tissue fragments in urine.

Advanced bladder cancer symptoms may include pelvic pain, bone pain, leg swelling (lymph node involvement), weight loss, and fatigue.

Late-stage indications may involve anemia and elevated blood levels of urea due to urinary tract obstruction.

Symptoms resembling those of infections and kidney stones require prompt medical attention for an accurate diagnosis.

Cystoscopic view of bladder cancer

patients with bladder cancer often present with visible haematuria

What happens after referral

After receiving your referral, our practice nurse will triage your case, and you'll be promptly contacted for a brief overview of your condition. Preceding your visit, several diagnostic tests, urine analysis, urine cytology ultrasound, and CT urogram are arranged to enhance the evaluation. At your appointment, A/Prof Homi Zargar will engage with you, conduct a thorough assessment, and review the gathered information. Very likely, your bladder will be assessed with direct visualization with cystoscopy in the office.

Treatment

The initial step in diagnosing bladder cancer involves a procedure known as transurethral resection of the tumour (TURBT). This procedure serves a dual purpose, functioning both diagnostically and therapeutically. Throughout the process, a bladder tumour, a common cause of haematuria (blood in urine), is meticulously resected or shaved off the bladder wall using a specialized telescope inserted through the urethra. Following the procedure, if determined to be safe, the bladder will be infused with a cytotoxic agent called mitomycin (MMC) to diminish the potential recurrence of bladder cancer in the future.

The excised tissue fragments are subsequently sent for pathology analysis to determine the cancerous nature of the tumour and assess its depth within the bladder wall. Depending on the findings, some patients may necessitate additional treatments such as chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or further surgery, while most patients require periodic follow-up with subsequent telescopic bladder examinations.

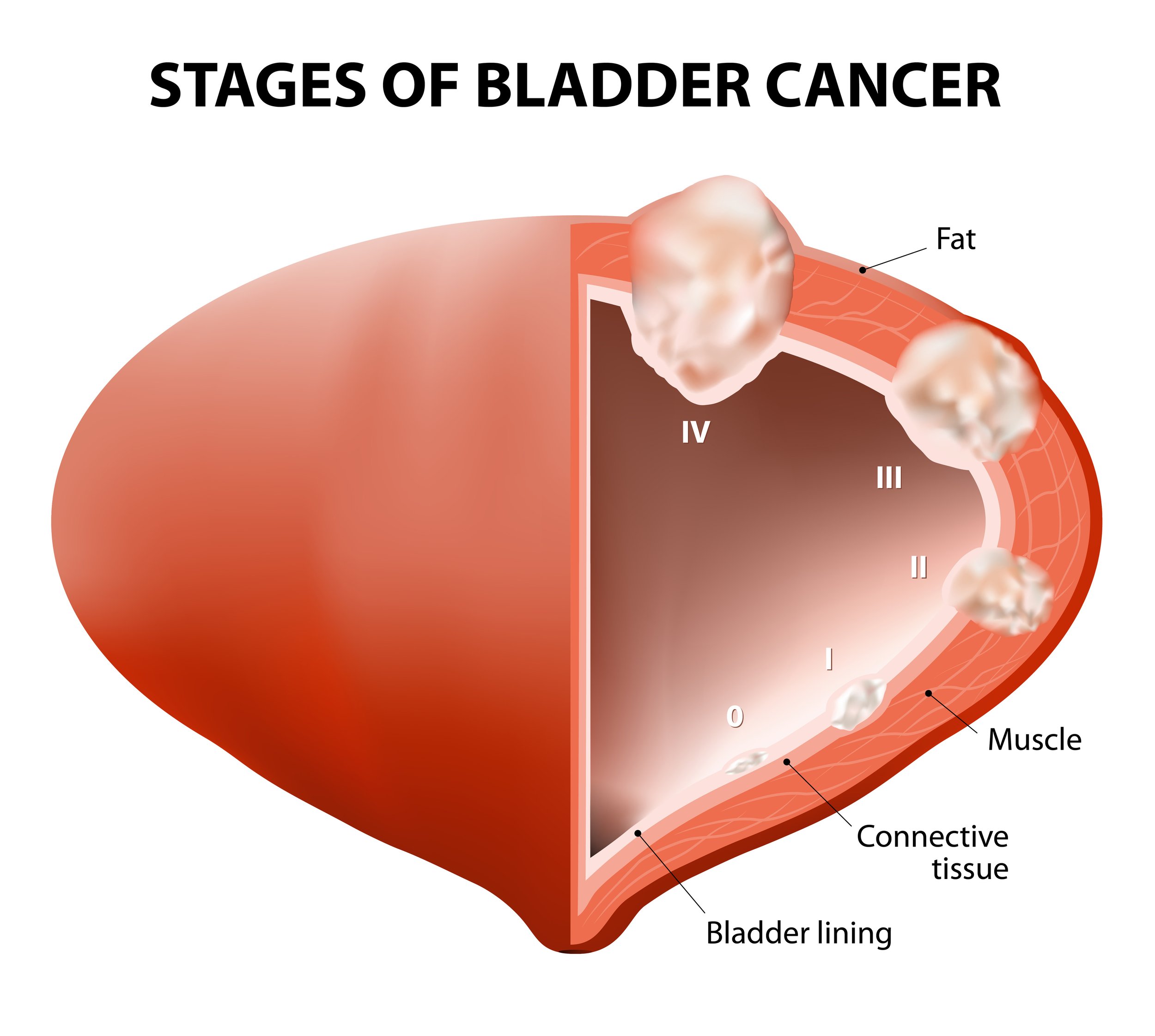

Pathological staging

The tissue extracted from TURBT undergoes comprehensive evaluation by pathologists to address key inquiries crucial for treatment decision-making. This examination determines the treatment algorithm, focusing on discerning whether the tumor is of low-grade or high-grade nature. High-grade tumors typically exhibit an increased likelihood of recurrence or progression, necessitating potential supplementary interventions. Additionally, the pathologist assesses the depth of invasion, determining whether the cancer has infiltrated the underlying tissues and muscles. This thorough analysis plays a pivotal role in tailoring an effective and targeted treatment plan based on the specific characteristics of the bladder tumour.

Superficial bladder cancer, which accounts for approximately 75% of newly diagnosed cases, remains localized to the bladder lining without penetrating the muscular wall. Initially, local treatments are employed for management. Among superficial bladder cancers, there are three primary categories. Non-invasive bladder cancer protrudes into the bladder cavity, resembling coral growth on a reef. Although they can attain significant size, the likelihood of transforming into invasive cancers is only about 5%. Treatment involves TURBT under general anaesthesia. However, recurrence is common, necessitating additional interventions for patients with frequent occurrences, large tumours, or adjacent carcinoma in situ (CIS).

Superficially invasive bladder cancer marks the penetration of the deeper layers of the bladder wall lining without reaching the muscle. Presenting a risk of further invasion and metastasis, 30-50% may progress to muscle-invasive tumours. Post-TURBT, intravesical therapy, involving the infusion of chemotherapy or immunotherapy drugs into the bladder, becomes necessary. In unsuccessful outcomes, more radical treatments are considered based on individual circumstances. Carcinoma in situ (CIS) denotes the transformation of the bladder lining into flat areas of cancer cells without visible growth. With a 50% risk of progressing to invasive cancer, intravesical therapy is employed.

Muscle-invasive bladder cancer poses a grave threat, having invaded the bladder muscle and risking spread to nearby structures and distant organs. Additional tests, including chest X-ray, bone scan, and CT scan, may be performed to assess potential metastasis. Surgical removal, often via radical cystectomy (complete bladder removal) or an alternative approach combining radiotherapy and chemotherapy, becomes necessary for effective management.

Suregry for bladder cancer

TURBT

Resection of bladder tumours involves shaving them off the bladder wall using a telescope inserted through the urethra.

The tumour removal may involve using different electrical modalities (unipolar or bipolar) or laser.

The tumour may be resected in one piece (en bloc) or often in multiple pieces.

Removed tissue fragments undergo pathology analysis to determine the cancerous nature and assess the depth of tumour invasion into the bladder wall.

Additional treatments such as chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or further surgery may be required for some patients.

Periodic follow-up with telescopic bladder examinations is recommended for most patients.

Read more about TURBT

Radical Cystectomy and urinary diversion

The objective of cystectomy is to achieve the removal of the bladder and the contained cancer and the surrounding lymph nodes.

In men, this typically involves the removal of the bladder, prostate, and local lymph glands to maximize cancer removal.

In women, generally involves removing the uterus (womb), ovaries, upper vagina, and local lymph glands to maximize cancer removal.

Following the removal of the bladder, urine diversion onto the abdominal wall is carried out using an isolated section of the bowel as a urostomy (ileal conduit).

In selected cases, a reservoir for urine is constructed from a section of the bowel connected to the urethra to form a "neobladder."

This procedure can be performed through an open or keyhole approach, often with robotic assistance.

Regardless of the approach, radical cystectomy is linked to notable morbidity, with the majority comprising minor complications; however, a small proportion of patients may encounter significant complications associated with the surgery.

Patients are often required to undergo 3-4 cycles of chemotherapy before their surgery (neoadjuvant chemotherapy).

Read more about radical cystectomy